Welcome to VERY LOST. I’m coming to you from Month 17 of my travel sabbatical, writing about the places that have shaped my understanding of how we live and interact. If you want to travel along with me, subscribe below.

Heads up: The essay below is heavy. It focuses on the 1992 - 1995 Bosnian Genocide, which I spent a considerable amount of time learning while I was in Sarajevo. If you choose to keep reading, thank you.

The man who took my clothes had no hands.

This is my introduction to Sarajevo, a city that had spent 44 months under siege, less than 30 years ago.

Survivors walk around the city —some who were only children then— with missing shins and long-gone arms. Bullet holes pockmark the buildings along Sarajevo's main thoroughway. Don't blame us if we don't smile at you, one woman tells me kindly. We all have so much trauma.

Sometimes, as I walk through Sarajevo's Baščaršija, or Turkish bazaar area, I forget this. I look wide-eyed at the tourist stands, the baklava shops, and the dominating, medieval architecture. Then, I remember.

I hand over my laundry to the man with no hands. He pushes them into a laundry basket with sharpie-drawn lines labeled 10, 20, 30. I give him 10 euros.

I spend the rest of the day visiting four —yes, four— genocide museums. That evening, our hostel owner, Igor, would greet my trembling lip with a Didn't I warn you not to do that?, followed by several shots of rakia, Eastern Europe’s favorite spirit. I would need it.

Bosnia & Herzegovina

My first evening in Sarajevo, I walk into our hostel’s common area, throwing down my backpack and crossing my legs on a floor cushion. My accent reveals my nationality, and one of my new hostel mates says, Your country is a mess right now, isn’t it?

I purse my lips, exhausted from my train ride, trying to formulate the best way to say, well, yes, while using as little energy as possible. Igor, thankfully, overhears our conversation. He exhales his vape pen and pops in from the patio’s open door.

You think America is bad? Have I told you about our system here?, he says.

Bosnia is made up of two separate entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (majority Bosniak), and the Republika Srpska (majority Serb). Sarajevo, the capital, is divided between them. The Republika Srpska flies the Serbian flag instead of the Bosnian one — they even had to switch it out before a visit from Biden.

That isn’t even the most confusing part. The country is led by three presidents representing three ethnic groups: Bosniaks (predominantly Muslim), Serbs (predominantly Serbian Orthodox), and Croats (predominantly Catholic). All three presidents must agree to enact policy — a strategy meant to prevent another civil war.

The only thing they’ve ever agreed on was cancelling Pride, Igor tells us, explaining Bosnia's convoluted system over another round of rakia. I look up at the rainbow flag hanging above the patio’s sliding doors.

The Bosnian Genocide

Back at the laundromat, I walk back to the hostel to meet two others. We walk the three blocks to Sarajevo’s Museum of Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide, promising each other emotional support as we braced ourselves for the visit.

I enter the first exhibit. Pictures of battered bodies line every wall. First-person stories lay below, painting the vivid memories of survivors. I inhale, and hold my breath. Don't read everything, you won't be able to handle it, Igor had warned us. I ignore his advice, until my stomach splits open and I can't ignore it anymore.

I don’t know much about the Bosnian Genocide. I try to make sense of the timeline, categorizing it against every other mass tragedy I’ve been forced to learn of.

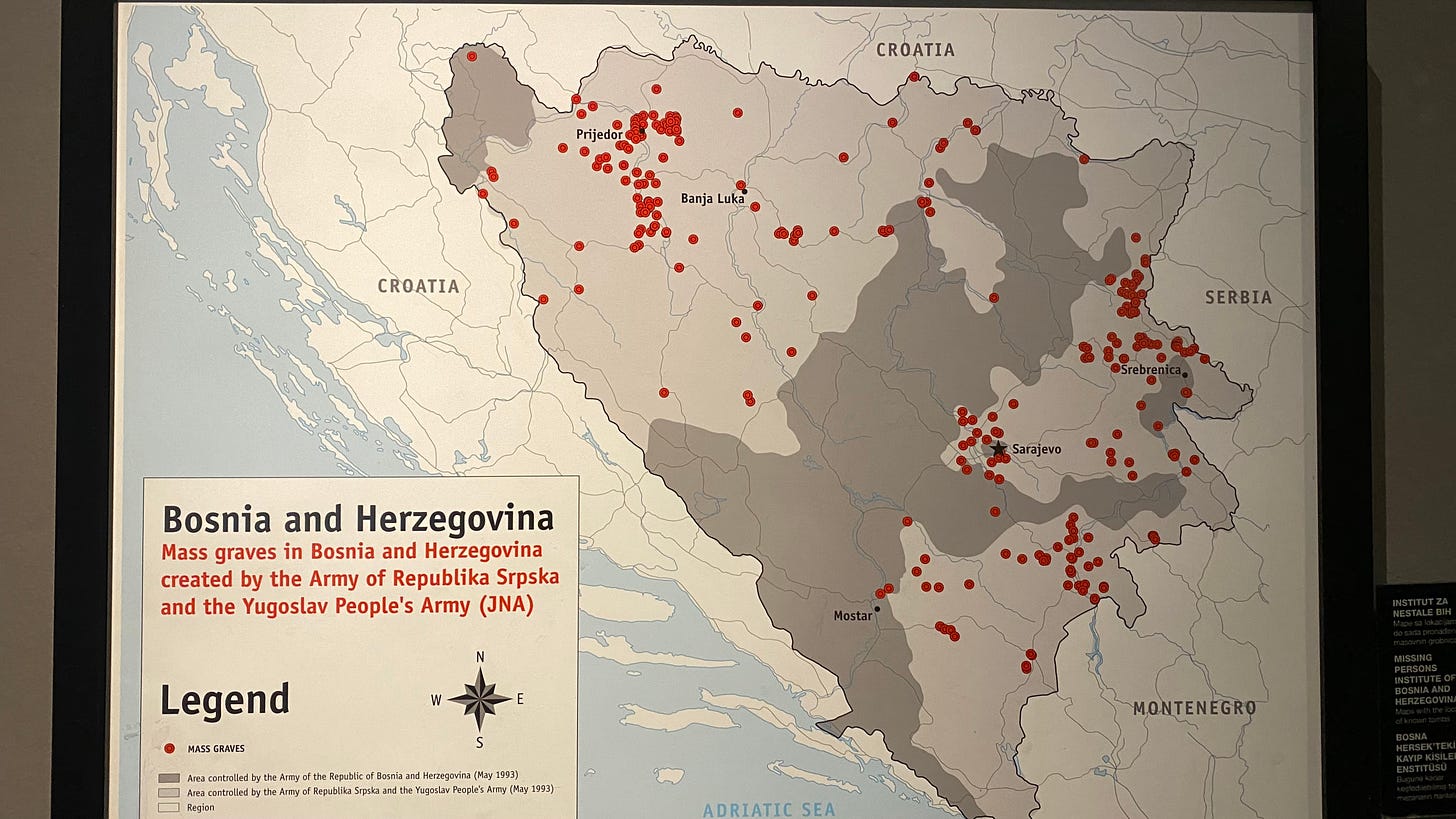

In 1992, Bosnia & Herzegovina declared independence from Yugoslavia, much to th displeasure of its Serb population. The Bosnian Genocide covers the widespread ethnic cleansing of Bosniaks (and, to some extent, Croats) by the Serbs during the 1992 - 1995 Bosnian war. Bosniaks are killed and terrorized en masse. Mass graves litter the country, from border to border. Over 8,000 children are born from genocidal rape, many of whom are looking for their fathers today. What kind of feelings do you have for a father born from this?, I wonder.

The most notable tragedy of the Bosnian War was the Srebrenica Massacre, where over 8,000 Bosniak men and boys were murdered in the town of Srebenica over six days. Snapshots of these victims, smiling and in their best dressed, line the first exhibit of Gallery 11/07/95. Tarik Samarah, a Bosnian and Sudanese photographer, captures stills of loss, of hope, of heartbreak in Srebrenica’s aftermath. I look at the photos of Srebrenica’s survivors taking the bus, drawing blood for DNA tests, and digging through the rubble for pieces of their loved ones. I circle the exhibit again and again. I stare at this picture of a mother and her child, clinging to a toy, and I hope with such silliness that my presence here will make them feel less alone.

The irony was that Srebrenica, a majority Bosniak Muslim town, had been declared a UN 'safe zone.' But when the Serbs attacked Srebrenica, Dutch peacekeeping soldiers didn’t offer citizens shelter or protection. In contrast, when the same Serb army attacked the town of Bihać near the Croatian border, French forces allowed Croat civilians into their compound, preventing a massacre.

Why?, is the question that echoes.

Denial is an integral part of genocide and includes the secret planning of genocide, propaganda while the genocide is going on, and destruction of evidence of mass killings. Complete annihilation of a people requires the banishment of recollection and suffocation of remembrance. Falsification, deception, and half-truths reduce what was, to what might have been or perhaps what was not at all.

Museum of Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide

The Siege of Sarajevo

I leave the Museum of Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide alone. Across the street sits the Siege of Sarajevo Museum, a combo ticket I had already committed to. I enter, promising myself not to read everything, because I already know I can't handle it.

I piece together the details of the siege. It stretched across 1,425 days — from April 1992 to February 1996 — the longest siege of a capital city in modern warfare. Serb forces deliberately targeted civilians with sniper shots and grenades; over 13,000 people were murdered. During the siege, Serb forces withheld gas, electricity, medical supplies, and water for months at a time — a strategy we’re seeing repeat throughout history.

To understand the siege of Sarajevo, you must understand how it is built, I read on a screen in the Siege of Sarajevo Museum.

When I leave the museum, I look around. Sarajevo sits in a basin, surrounded by hilltops and mountain ledges where the Serb army stationed, readying their aim at citizens walking the streets. I look up at the Yellow Fortress, where tourists and teenagers now climb to for sunset, and imagine a sniper there, taking aim at my forehead.

In the period covered in this indictment, there was no safe place for the people of Sarajevo, not at home, school, hospital, from a deliberate attack. Prosecutors Summary, Indictment against General Galic, ICTY

IV. A Children's War

Throughout the war, Serb forces shelled children's wards in hospitals daily; on one of the siege's first days, they destroyed Sarajevo's maternity ward.

All the genocide museums in Sarajevo tell the stories of children targeted by Serb forces as they played outside, walked to school, or slept at home. One panel tells the story of a boy who wasn't allowed to play outside one day, watching from his bedroom window as his friends are killed by a grenade. Another tells of a girl who saw a grenade fall on her parents, her grandmother holding her back from running out to 'save' them.

I walk into the War Childhood Museum, my third museum of the day, finding comfort in the Museum's child-friendly approach in portraying war from the eyes of children. Exhibits highlight the items that brought children comfort: a bright blue stuffed bunny, a can of biscuits, a first pair of Levi's.

Beside fragments of a playground set, Haris Barimarc tells the story of another close call:

And just before we started to play, a grenade hit that structure we had just moved away from. It was 2:50pm. The detonation knocked me to the ground and I lost consciousness... On that day, Azmir Bradarac (1976), Sanela Hadžiomerović (1978), Aldina Čolpa (1979), and Admir Ċolpa (1985) were killed at those chin-up bars. Dženita Hadžiomerović, Adriana Gilgorijević, and I, Haris Barimarc, were all wounded by the shrapnel.

War Childhood Museum

I move onwards, and stand solemnly for several moments in front of the contemporary exhibit: three items from children of Palestine and three from children of Ukraine.

I think about how the Bosnian genocide is often framed as a European anomaly. Can you believe this happened in Europe?, one tour guide had told me. On a civilized continent like ours?, seem to be the words underneath.

I imagine a future where, I hope, Sarajevo has healed, but another city is flooded with adults — only children at the time — with missing shins, long gone arms, yet again. I wonder how long it takes for a tragedy to become a history, a 'lesson learned,' a 'never again.’ I become angry that we have to wait for this. I become angry at the cycle.

I walk back to my hostel as the sun sets, texting a friend that I’m too nauseated to meet her for dinner.

You look bad, H. says to me as I sit down at the hostel’s kitchen table and give him a half-hearted smile. I tell him what I had been up to. Igor overhears our conversation from the patio, snickers at the emotional whiplashing I put myself through that day, and pours all of us shots of rakia.

In total, I spent 4 days in Sarajevo, much of it focused on war tourism. But still, Sarajevo — and Bosnia — has so much more to offer than its scars: beautiful architecture, glistening lakes, sweeping mountains.

The next afternoon, I sit on the patio with Igor, admitting that I felt guilty spending so much time on Bosnia's darkest moments. Was war tourism even ethical?, I asked him.

You Americans think too much, he laughs at me. We want what happened to be remembered.

We also want your money, he adds with a wry grin.

I relax.

You are now leaving the Museum of Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide, 1992-1995. Thank you for 'giving life' to human hearts that no longer beat. May those hearts lead you to times without pain, suffering, and cruelty towards each other.

Museum of Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide; Sarajevo, BiH

Thank you for reading VERY LOST. A special thank you to those who have become paid patrons of VERY LOST, who receive paywalled essays and other perks.

Some reads from the past few weeks that I’ve loved:

- ’s essay on translated works and relationship with the poetry of her mother tongue

- ’s reflection on loveless games

- ’s memoir on the home she loves in a place that doesn’t love her back

"But still, Sarajevo — and Bosnia — has so much more to offer than its scars..."

This felt like poetry friend. Props for diving into such a heavy space, and so fully.

Thank you Zefan. Beautifully navigated through a horrible topic.