Tomorrow, May 24, is Eritrea’s 33rd Independence Day.

A couple of days ago, I bathed in the romance of sitting on a European train while staring at Bulgarian countryside. On my mind lingered Eritrea’s upcoming independence day, as well as thoughts of belonging. My Eritrean identity had built the foundation of my paradigm. This means that, sometimes, I don’t feel like I belong to other communities I love.

As I thought about belonging, Nipsey Hussle’s Victory Lap jumped into my AirPods.

Nipsey, or Ermias Asghedom, had become an icon for American-born Eritreans, both in life and death. A Grammy-award winning rapper, entrepreneur, and community leader, he also dedicated his life to the predominantly Black American communities in South Los Angeles — and they revered him for it. He existed as both Eritrean and American, flawlessly.

When I see Ermias, I see the story of Eritrea, the spirit of the Eritrean people. He reminds me of how Eritrea shows up in me, and in all of us, no matter what soil our feet stand on.

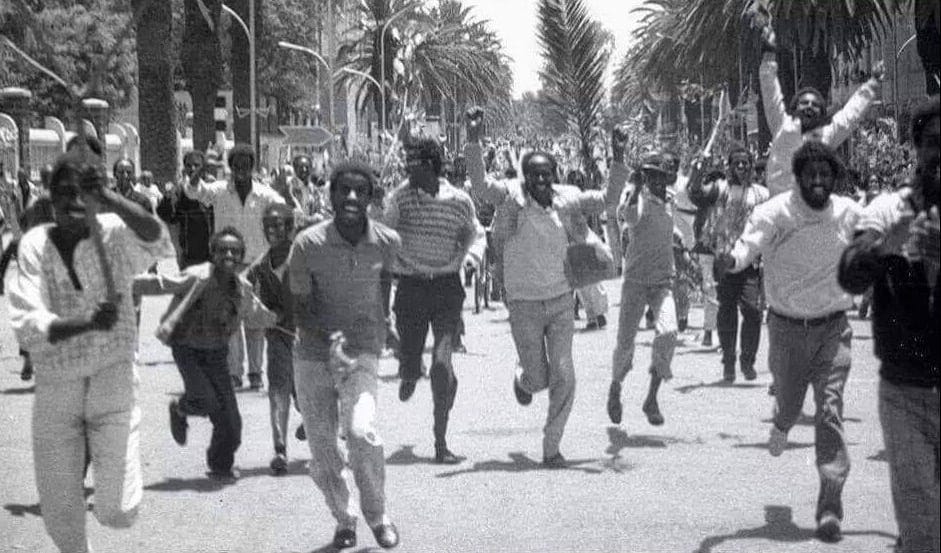

Ghedli

Eritrea’s struggle for independence (1961 - 1991) is one of the longest armed struggles in the world. After five decades of Italian colonization, Great Britain seized Eritrea after Italy’s loss in World War II. In their all-knowing wisdom (cue sarcasm), Great Britain and the United States federated Eritrea with Ethiopia, against the will of Eritrean parties pushing for a referendum. By the end of the decade, Eritrea’s largest university had birthed the Eritrean Liberation Movement. For the next thirty years, liberation parties used fiery spirit and guerrilla warfare to fight two superpower-backed Ethiopian regimes (a U.S.-backed monarchy, followed by a Russia-backed Marxist dictatorship). After thirty years, Eritrea won. Against all odds, we often shout to the world.

Eritrea’s armed resistance spans multiple generations. Every single family experienced loss in those 30 years, a weight heavily woven into our identity. This ghedli, this shared struggle, binds us.12

In Nipsey, I also saw ghedli. Growing up in Crenshaw, he spent his formative years engulfed by gang violence and turf wars. Eventually, he joined the Rollin’ 60s Crips.

“As gang members, as young dudes in the streets, especially in L.A., we’re the effect of a situation. We didn't wake up and create our own mindstate and our environment; we adapted our survival instincts,” said Nipsey.3

Ghedli means struggle, but it also means resilience. The resilience to survive, to adapt, and to prosper despite what you are given. Our tegadelti, our freedom fighters, refused to accept the environment they were given, despite the tremendous cost of resistance. Nipsey did the same.

Self Reliance

“Eritreans kneel on only two occasions: when we pray and when we shoot,” my father would say to coax bravery into me, quoting an Eritrean proverb born of the ghedli era.

My father, like Eritrea, champions one value before all else: self-reliance.

After decades of rule by the British, Italians, and Ottomans, Eritrea built an identity of never kneeling down, of never relying on anyone but herself. In the ghedli era, militias built self-reliant systems from the moment an area was liberated: schools, clinics, agricultural and water management systems. They ran their own underground networks across the country for food, healthcare, education, and communication. The resistance party that brought victory to Eritrea, the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front, strategized on how to get there without depending on external monetary or material support. Today, Eritrea’s self-reliance is still the cornerstone of both foreign and domestic policy. This makes her either isolationist or a fight against African neocolonialism, based on your paradigm.

In Nipsey, I saw the stubborn self-determination that I was raised with, the scowl at relying on anybody outside of ourselves. “Made my first million on my own, I don’t need your help,” Nipsey raps in Blue Laces 2.

How Eritrean, I remember thinking when I heard that he built his own independent music label back in 2010, refusing to kneel down to the traditional music industry and their obscene ownership rights. It was Eritrean self-determination, too, that I saw in Nipsey’s investments in his community. In 2017, he opened up The Marathon Clothing store, dedicated to providing jobs and a gathering space to the South LA community. He invested in schools, parks, and community spaces, and had plans to build affordable housing units. Much like Eritreans sprung up to build self-reliant systems in liberated areas, Nipsey built his.

Unity

My father, by all definitions, is a staunch Eritrean patriot. When we wrestle together over Eritrea’s place in the world — its past sins, its future wins — he jumps to remind me of one of his greatest prides of our homeland: unity. Across ethnicity and religion, we refuse hate-based violence. Our unity will never be compromised.

Nine ethnic groups come together to create Eritrea: the Tigrinya, Tigre, Saho, Afar, Bilen, Kunama, Nara, Rashaida, and Hidarab. Two religions dominate Eritrea: Christian and Muslim, at precisely 49% each. Despite these differences, neither ethnic nor religious conflict has yet to stain our legacy.

During the armed struggle era, the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front held a motto close to their chest: “unity in diversity.” Before DEI was a thing, The EPLF used diversity councils — made up of reps from all ethnic groups and regions — to guide decision-making. Leaders were chosen by merit, not affiliation. EPLF not only operated multilingually, but built language schools and cultural festivals to preserve all facets of Eritrean identity. Women, too, were celebrated, making up 30% of the EPLF and holding significant leadership positions. Today, my father and I still smile about the Cathedral and Mosque in Eritrea’s capital of Asmara, sitting within shouting distance. Streets fill, both on Easter and Eid, as Eritreans shout joyfully for the holidays of their neighbors.

After Nipsey’s death in 2019, L.A.’s most notorious gangs, the Bloods and the Crips, called a truce to march together for Nipsey’s memorial. It was the first truce since the 1992 Rodney King protests. A former Rollin’ 60s Crips member, Nipsey famously performed with both Crips and Bloods. He actively facilitated truces among different South L.A. factions. He invested in and mentored former gang members regardless of their alliances. A year later, over 30 L.A. gangs had agreed to a prolonged ceasefire in honor of Nipsey’s legacy. “I think the progress that’s been made in the last year is the most that we’ve ever seen in the history of Los Angeles,” said an L.A. gang expert. Nipsey’s thirst for unity was so unquenchable that it continued after his death.

Nipsey’s father and mine, born of the same generation, were classmates in Asmara. Nipsey and I spent the same summer — the summer of 2004 — back home in Eritrea. It wasn’t until today that I learned our shared summer is what inspired Nipsey to build a new reality in South L.A.

Struggle, self-reliance, and unity are what bind Nipsey — and me — to Eritrea.

By tomorrow, I’ll have been traveling around the world for 15 months. My ghedli, my struggles, are nowhere close to Eritrea’s or Nipsey’s. But, I’d like to think that my spirit still is. Fifteen months ago, I picked up my backpack because I had refused to accept the environment I’d been given. I created my own reality, my own plan, my own template for what life and career should look like. My self-reliance has carried me through this adventure solo, and has helped me build a community of support to see it through. My thirst for unity has led to knowing and understanding people in countries I hadn’t dreamed of loving.

As I looked out the window at the Bulgarian countryside, I thought about what Eritrea had given Nipsey and I. He used it to create community in South L.A., and I can use it to create belonging in any community that I choose to call home.

For my ghedli, my self-reliance, and my thirst for unity, I am grateful.

To all those who celebrate this weekend, Happy 33rd Independence Day.

Awet N’Hafash — victory to the masses.

Thanks for reading. For republication requests, please contact zefan@duck.com.

It was very difficult here to not go into details about my own family’s story. Perhaps I’ll dive into that in future essays.

In addition to the 30-year war for independence, there was a significant border war with Eritrea from 1998 - 2000 that I have not included here.

This quote was found on several websites, but I couldn’t find a primary or official source.

I love how you are thinking about place, ancestry, & hip hop. I'm honored to learn a small piece about your family history & how Eretria as a site of memory/knowledge shaped both you & Nipsey. The marathon continues in L.A., your family, your work, & where your feet are planted 💙. Keep doing it "real big!"

'...a fight against African neocolonialism...'

It really is sad and angering when you think of the utter damage brought upon African nations due to both colonialism in the past as well as the current neocolonialism, in which the main parties that benefit are the multinational corporations and certain global institutions.

Insightful and inspiring article on Eritrea’s struggle for independence and on Nipsey, Zefan. Thanks for sharing this.